Our President and Chief Admissions Consultant, Dana Crum, has helped innumerable high-school seniors with their college essays. Below is his college essay – except its intent is not to convince a college to admit him. It focuses instead on the college he attended and explores his status as an alumnus who is seldom there now but was forever changed by his time at the school. In the essay he also recognizes that what his alma mater means to him differs from what it means to his fellow alums—a recognition that enables him to more fully appreciate the subjectivity of psychological truth. It’s something nearly every Princeton alum has experienced. This feeling—while visiting campus—that the school is no longer yours, that it now belongs to the students streaming out of newly built Whitman College or typing notes in grand but frowsy McCosh 22. You envy these students’ youth. Certainly. But you also envy their enrollment. Now it’s they, not you, who peruse Herodotus on the bottom level of Firestone and party in 81 Spelman; they, not you, who enter the modern-day Parthenon that is Robertson and traipse beneath the rain, the Gothic dorms wet and a darker shade of gray. As you plod past Whig and Clio, you feel not just older but invisible, like some tired ghost—or if visible, immaterial, no longer part of the school’s intellectual and social engine of precepts and exams, papers and problem sets, eating clubs and late-night Wawa trips. But, in truth, there is more than one Princeton. There is the Princeton of the student. There is also the Princeton of the alum. And just as the students’ Princeton is no longer yours, your Princeton is not yet theirs. They know nothing of Reunions, where you dance under a tent, cup of beer in hand, and discover that yes, you do still have a few moves left; where you chat with classmates you haven’t seen in years and leave (apologetically) every ten minutes to feed your wailing infant or change his sagging diaper; where you encounter classmates who look great (for their age) and classmates, who, let’s be honest, look like hell. (But who are you to talk? You’ve lost all your hair.) And they most certainly know nothing of Advanced Parenting Calculus, which you studied: a) to figure out just how you’re going to pay your daughter’s unwieldy tuition bill; or b) to become so rich that the punch the bill packs feels more like a pinch. As these varied Reunion experiences suggest, there is more than one Princeton among alums. Similarly, there is more than one among students. Because I grew up in inner-city DC, my Princeton experience was, let’s say, a tad different from that of many. Academically, I loved the school right away. But outside class and sometimes in, I felt dull and uncultivated. Many of my classmates—at the time, it felt like all—had summered in Saint-Martin, skied the slopes of Innsbruck and experienced the sublimity of La Bohème and Salome. They had attended schools like Choate and Stuyvesant, had no (discernible) gaps in their academic preparation and could speak with great eloquence. At my inner-city high school, many of my peers had given me a hard time for sometimes “speaking proper.” At Princeton, my classmates spoke that way practically all the time. DC was segregated even in the late 80s, so in high school it was mainly at scholarship receptions in my senior year that I interacted with whites. Uttering words I used mainly when writing, they so thoroughly enunciated and so consistently exercised correct verb conjugation that it had seemed they were speaking a kindred but distinct language, like Portuguese instead of the anticipated Spanish. Conversing with them revealed I couldn’t speak standard English for long without feeling pressure on my lungs and aching to come up for air, to breathe the protean, metaphoric idiom that is “black English.” (Admittedly, “black English” is problematic: not every black person uses it, it varies by region and some blacks reject the concept altogether.) By freshman year at Princeton, I could remain submerged longer. But not as long as my new classmates. So I worked harder, and soon I could remain submerged all day. This achievement, along with my grades, gave me confidence, which combatted the inferiority I felt for not having experienced operas and traveled overseas. And I learned to value my inner-city background and the rich cultural experiences it did provide. The perspicacity I demonstrated in precepts and the unique lunch-table contributions I made as someone who could quote, in the same breath, Slick Rick and T.S. Eliot earned me a place in the school’s student community. Upon graduation, Princeton was my Princeton, too, and it remains one of the most treasured experiences of my life. To the relief, indifference or scorn of some, I am neither the first nor the last black male to enter Old Nassau by way of the inner city. As a sophomore, I got to know a freshman with the “same” background (he grew up in Brooklyn). His Princeton experience was both similar and different. Character traits, in combination with other factors (when you attended, hometown, race, class, gender, sexual orientation), make it such that any number of Princetons are possible. An alum who is an administrator on campus shared an anecdote: during Reunions some older alums grumbled that the student body looks so different now, that it has so many people of color. The administrator responded that the student body should look different since our country looks different. (The U.S. Census Bureau projects that by 2044 whites will be the minority; people of color, the majority.) Perhaps, there are also alums who bemoan that the school now has more women and more individuals who are openly gay, lesbian, transgender or genderqueer. But Princeton does not belong to any single person, group or generation. The school must evolve as the country evolves. That it does explains, in part, why it abides as a preeminent institution of learning, as what any sensible alum would agree is a constant but ever-changing gathering of some of the best young minds in the country and the world. Though there are many Princetons, there is still one. And this Princeton makes the many possible. It exists not in spite of but because of the many, which together form, however improbably, a harmony beyond discord. An introduction typically opens with several sentences that get the reader’s attention and concludes with the thesis. The opening sentences should set up the thesis. Here is an example of an introduction (the thesis is italicized):

The above introduction sets up the thesis by presenting an overview of alternative critical interpretations, interpretations which the thesis pushes against. When writing the sentences preceding the thesis, I hoped that a brief look at the Romantic and psychoanalytic interpretations would interest the reader. However, your introduction’s pre-thesis sentences can hook the reader in many other ways – for instance, by using or including one of the following:

Notice how short this introduction is. Such brevity is not uncommon in work settings.

I received these paper-grading guidelines when I was an undergraduate at Princeton University. They were so helpful I held on to them and used them when I myself began teaching English. After all these years, I still have them and still find them illuminating. These guidelines are useful not only to students and teachers but also to professional writers, who even at their advanced level of proficiency can benefit from measuring their work against these high benchmarks. PAPER-GRADING GUIDELINES “D” Essays and Below These are some of the general tendencies that mark inferior writing:

“C” Essays CONTENT: The writing may be padded and repetitious, and the tendency to keep thought on a high level of generality without sufficient reference to detail or specific supporting illustrations causes the prose to seem thin. There is little indication of the writer’s intellectual involvement with the subject. Summary will predominate over analysis. The surest mark of a “C” essay is the preponderance of self-evident statements—all true, often clearly phrased, but predictable and often trivial. FORM: Most “C” writers will reveal that they are aware of organization, but to them form is formulaic. They have real difficulty envisioning form as setting a direction for thought, or as a way to set expectations for the reader. DICTION: “C” writing depends on the cliché. Lapses into jargon, and/or rapid shifts between the highly formal and the markedly colloquial, are common. The diction of the “C” essay is best explained as having a lack of range. The writing is undistinguished because the writer has limited verbal resources with which to work. MECHANICS AND STYLE: “C” writing may be perfectly correct, but often lacks a sense of ease with language—at best, perfunctory and uninspiring. “C” QUALITY WRITING USUALLY DEMONSTRATES:

“B” Essays CONTENT: The material of the “B” essay shows signs of independent thought and gives evidence of the writer’s active engagement with the topic. Something illuminating is said, in the sense that an insight is presented in such a way that the reader sees anew. FORM: “B” writers show a clear sense of order. They are conscious of planning and crafting their material to relate it to the central point or thesis being presented. Their formal control should also show evidence of transitions and thematic and verbal echoes that hold the thoughts together. DICTION: “B” writers, like “A” writers, have developed a vocabulary that allows them choices, and a sense of linguistic variety and freedom. They are able to select the “right” word or turn of phrase from a wide range of possibilities. MECHANICS: “B” writers turn in clean, correct essays. Few errors in the prose interfere with the writer’s thoughts. Control of grammar is sure. STYLE: “B” writers are aware of rhetorical strategies and can often call on devices such as parallelism, repetition, contrast and the rhetorical question with effect. Mature use of subordination permits concise, varied prose. The “B” essay has both distinguishable strengths and flaws, but the flaws are not so numerous or serious as to throw doubt upon the writer’s proficiency. The writer is in control, investing the essay with purpose, direction and strategy. “B” QUALITY WRITING USUALLY DEMONSTRATES:

“A” Essays The clearest difference between the “B” writer and the “A” writer is that the “A” writer often brings intellectual and imaginative resources to the task of writing in order to transform both material and language in some unusual way. “A” writing is usually distinguished by:

Perhaps the most marked characteristic of the “A” writer is the inability to suppress the personal voice—the sense of a lively intelligence behind the page—whether such emerges through viewpoint, metaphor, vocabulary or any other quality that announces the writer’s individuality. “A” writers have something worthwhile to say, and say it. They read perceptively, support their insights with judiciously selected evidence, and often respond by linking ideas with other ideas, books with other books. What they see is unexpected, what they write is fresh.  Courtesy of geograph.org.uk. Courtesy of geograph.org.uk. Literary critics and layman alternatives such as SparkNotes and CliffsNotes will—with varying degrees of accuracy and depth—summarize and analyze scenes from Shakespeare’s plays. Even when these sources get it completely right—and they don’t always—they don’t necessarily leave you with permanent skills so that you can decipher Shakespeare’s language on your own. Accounting for inversion (words and phrases in places you don’t expect them) is one of several strategies that can help you understand what the great Bard intends to convey. In Macbeth, when King Duncan sees one of his wounded soldiers, he declares: He can report, As seemeth by his plight, of the revolt The newest state. With phrases moved into positions we’re more accustomed to, the passage might read like this: As seemeth by his plight, He can report the newest state of the Revolt. Or: He can report, As seemeth by his plight, the newest state Of the revolt. So why does Shakespeare place phrases in such odd positions? Partly for emphasis. Partly to maintain each line’s iambic-pentameter structure. If these lines were from one of his sonnets or from a rhymed section of Macbeth for that matter, rhyme (i.e., getting words into rhyming position at the ends of lines) would likely have been an additional factor. Let’s examine a longer passage from the same play: Brave Macbeth,—well he deserves that name,-- Disdaining fortune, with his brandished steel, Which smoked with bloody execution, Like valour’s minion carved out his passage Till he faced the slave. Moving phrases around in line four helps clarify matters: Brave Macbeth,—well he deserves that name,-- Disdaining fortune, with his brandished steel, Which smoked with bloody execution, Carved out his passage like valour’s minion Till he faced the slave. Even with the change in line four, this sentence remains complex given that the subject, Macbeth, is still separated from its verb, carved, by two and a half lines, a reality that certainly challenges comprehension. Be that as it may, the change in line four has at least peeled away one layer of reading-comprehension challenge. Anticipating Shakespeare’s profuse use of figurative language and translating such passages into something more prosaic can also aid understanding, but that is a subject for the next blog post.  Just because you care about your students and yearn to see them succeed doesn't mean you don't sometimes chuckle at some of the mistakes they make in their writing. Below are some unintentionally amusing passages from student essays. Each passage is guilty of a forced simile. As any good English tutor (or editor) knows, it's better to use no figurative language than to use it badly.

Whether you’re a writer or editor, student or teacher, you may sometimes wonder how to explain “voice” or how to use it effectively in your writing. There are two major definitions of the term:

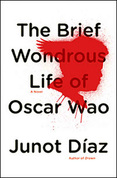

Aside from defining “voice,” the below slideshow does three things. It explains that voice is created by the writer’s diction, syntax (including sentence length) and tone; examines the often false dichotomy between voices that are written/formal and those that are spoken/informal; and provides several examples of first-person prose, each exhibiting a different voice. Examples include excerpts from the following texts: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz, Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, “On Being a Cripple” by Nancy Mairs, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “Mother to Son” by Langston Hughes, Edisto by Padgett Powell, Notes from the Underground by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros and “Issues I Dealt With in Therapy” by Matthew Klam. In its examination of “voice,” the slideshow focuses mainly on the second definition above, but its findings are also relevant to an understanding of “voice” as defined in the first definition. View the slideshow here: Download the file:

Image courtesy of drsimpson.net. Image courtesy of drsimpson.net. by Dana Crum Every professional must write well, not just writers.1 Don’t think you are the exception to this rule because all you write is emails or memoranda. Your email could inadvertently offend a client and lose you business. A confusing or inadvertently misleading memo could cause coworkers or subordinates to execute project tasks incorrectly, wasting time and money and perhaps losing you business. That reports, presentations and website copy should be well-written is more self-evident. Just in case it’s not, imagine you own an Internet-strategy consulting firm. A potential client visits your website, sees innumerable grammatical errors and misspellings, and wonders what else you do badly. For fear of finding out, she decides not to hire you. Your writing will improve exponentially if you get into the habit of using specific nouns and vigorous verbs. Nouns and verbs are the most important parts of speech—think of them as the chief building blocks—and generally the best nouns and best verbs are specific and vigorous, respectively. A noun names a person, animal, place, thing or abstract idea. In the context of a sentence, it states who or what is involved in the action or who or what is being described. The importance of nouns explains why they are typically the first words children learn. To see how general nouns can weaken your writing, consider the following sentence, which a zoologist might write: The animal can reach a top speed of 79 mph. Animal is much too vague. It calls to mind no image, a vague image or an image different from the one the zoologist intends. And the reader is left wondering what animal moves at that speed. Is it the cheetah? But then again, don’t cheetahs max out at 75 mph? The below revision clarifies matters: The gyrfalcon can reach a top speed of 79 mph. The above revision not only clarifies which animal is under discussion. It also puts the cheetah in its place as simply the fastest land animal, outpaced by the gyrfalcon (which is in turn outpaced by the fastest animal of all, the peregrine falcon, which reaches 242 mph as it dives toward its prey). Specific nouns are usually better than general ones. But not always. Let’s return to our zoologist. Let’s imagine she writes: An animal is a multicellular living thing that differs from a plant by having cells without cellulose walls, by lacking chlorophyll and the capacity for photosynthesis, by requiring more complex food materials such as proteins, by being organized more complexly, and by having the capacity for spontaneous movement and rapid motor responses to stimulation. Here our zoologist is justified in using a general term like animal because she seeks to supply a definition that encompasses animals as diverse as vertebrates, mollusks, arthropods, annelids, sponges and jellyfish. In short, she needs an incredibly inclusive term. Animal qualifies. Specific nouns are not only typically better than general ones. They also reduce wordiness. Okay, so let’s pick on historians, for a change. A member of their field might write: In a long, angry piece of writing the prime minister accused the neighboring country of ceasing to patrol the border, thereby allowing guns to pour into his war-torn nation. The underlined phrase contains five words: the general noun piece, the adjectives long and angry, and the prepositional phrase of writing, which functions as an adjective and culminates with the general noun writing. The historian has used five words (and seven syllables) to say what could have been said in one word (and one syllable): In a screed the prime minister accused the neighboring country of ceasing to patrol the border, thereby allowing guns to pour into his war-torn nation. A simpler type of wordiness—one or more adjectives joined with a general noun—can also be eliminated with a specific noun: For instance, large book can be changed to tome. Whichever parts of speech are implicated, wordiness is a sin committed daily. Verily I say unto you, Except for rare occasions, thou shalt not use many words when one will do. (Our historian is also guilty of using the hackneyed war-torn.) Now that we’ve examined nouns, let’s turn our attention to verbs. There are two types: action and linking. An action verb—surprise, surprise—conveys action. A linking verb such as to be expresses a state of being, functioning like an equal sign, linking the subject either to another noun that re-identifies it or to an adjective that describes it. Because they express no action, linking verbs weaken your writing when used often. So, for the purposes of this installment of this column, when I say verb, I mean action verb. If a noun provides information on who or what is acting or being acted upon, a verb describes the action and supplies the power that drives the sentence. The difference between a vigorous verb and a weak one is the difference between a punch and a tap. Even if you need to describe a gentle action, you should probably do so forcefully: She placed her half-parted lips against his. Placed will not do. It does not have the delicate, romantic connotation the scene requires. Nor does it have much vigor. Here’s an improvement: She brushed her half-parted lips against his. Brushed may not be perfect, but it’s better than the original verb. It’s also better than a vigorous verb a clumsy writer might use: dragged. When the action is not gentle or delicate, a vigorous verb is needed as well. A novelist, describing a highway scene, might write: An eighteen-wheeler sped past, loud like some heavy, sluggish rocket. Sped isn’t bad. But it’s not great. A more vigorous verb is called for, one that conveys the speed particular to a vehicle that because of its size has more momentum than a much smaller vehicle traveling at the same speed (momentum, you will recall from physics class, is calculated by multiplying mass and velocity): An eighteen-wheeler hurtled past, loud like some heavy, sluggish rocket. Let’s say the same novelist describes a character speeding through a tunnel in a Mustang GT: The ceramic walls of the tunnel moved past in a white blur. Moved is general, weak and boring. Zoomed is better but cliché. The below revision uses a verb that is vigorous and original and that captures the play of light: The ceramic walls of the tunnel glinted past in a white blur. Like specific nouns, vigorous verbs often reduce wordiness. When they do, the combination of concision and force creates a particularly vigorous effect. Let's say a technology blogger writes: The Internet radically and completely changed commerce and communication. One vigorous verb could be substituted for four words—the adverbs radically and completely, the conjunction and and the verb changed—channeling more force in a smaller space, amplifying the power: The Internet revolutionized commerce and communication. Generally, you should never use a verb and one or more adverbs when one word—namely, a vigorous verb—can convey your intended meaning. Just as there’s a time to use general nouns, there’s a time to use weak verbs. Let’s return to our zoologist. Let’s say she wants to discuss the various ways in which humans locomote. She might introduce this topic with a sentence like this: Homo sapiens walk in various ways. She might follow this sentence with one that lists types of walking, using a vigorous verb for each: Depending on their age, physical fitness or inclination on a given day, they will, for example, saunter or sashay or stride or plod or stomp. In this sequence of sentences, our zoologist has skillfully used not only several vigorous verbs but a weak verb as well. Specific nouns and vigorous verbs help make your writing concrete, which is generally preferable to it being abstract. Concrete words--eighteen-wheeler, falcon, stomp—appeal to the senses and enable the reader to imagine what’s being discussed. Abstract words--transportation, life, perambulate—refer to relatively vague ideas and concepts, do less to stimulate the imagination and carry less emotional impact. Concrete comes from a Latin word meaning grown together, hardened. Abstract comes from a Latin word meaning removed from or removed from concrete reality. Remove your reader from concrete reality too often, and you will remove her interest in your writing. Ezra Pound advised poets to “go in fear of abstractions.” His advice should be heeded not just by poets but by anyone who puts pen to paper or, to update the image, fingertips to iPad. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 The only way around learning to write well is to have contractors or subordinates write for you. Just make sure they know what they’re doing.  Here are actual statements from auto-insurance forms. Each driver tried to summarize his accident as concisely as possible. While space constraints might have contributed to the poor writing quality, it's undeniable that these hapless souls struggle to express themselves clearly and logically. If their writing reminds you of your own, consider hiring a Prose Wizard editor, writing coach or tutor: 1) I was on my way to the doctor with rear end trouble when my universal joint gave way causing me to have an accident. 2) The guy was all over the road. I had to swerve a number of times before I hit him. 3) The pedestrian had no idea which direction to run, so I ran him over. 4) I had been driving for 40 years when I fell asleep at the wheel and had an accident. 5) An invisible car came out of nowhere, struck my car and vanished. 6) I was thrown from my car as it left the road. I was later found in a ditch by some cows. |

A blog about Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

||||||||||

Company |

|

© Copyright 2015. Prose Wizard. All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed